1968 Exhibition of Contemporary French Painting

12.11 – 03.12.1968 1968 Exhibition of Contemporary French Painting

Zachęta Central Bureau of Art Exhibitions (CBWA)

organiser: Création Artistique, Ministry of Culture and Arts, Central Bureau of Art Exhibitions

commissioner: Bernard Anthonioz, deputy commissioner: Maurice Allemand

exhibition design: Stanisław Zamecznik

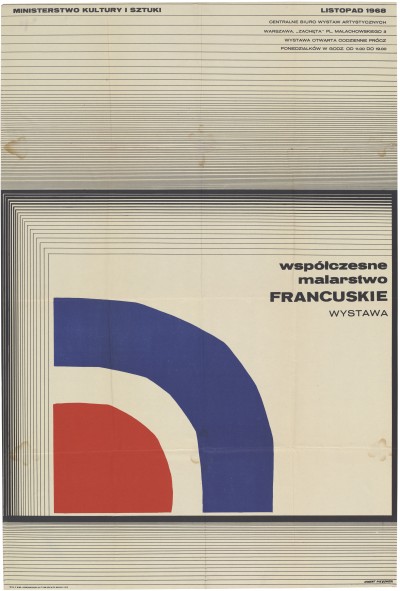

poster design: Hubert Hilscher

catalogue graphic design: Stefan Bernaciński

In the introduction to the catalogue of the 1968 Exhibition of Contemporary French Painting, deputy commissioner Maurice Allemand stated ‘We hope that the collection of works represented here will not be a source of disappointment’.[1] By reviewing the press mentions regarding the exhibition, one may come to the conclusion that the reality did not live up to his expectations. The exhibition was often compared to the Contemporary Trends, which were presented two years earlier, prepared especially for the Polish audience by Edy de Wilde, director of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam.

Ignacy Witz stated, ‘The bitter words that I write about the French exhibition stem not from the fact that we were shown bad paintings by bad painters. Quite the contrary — we were shown average paintings by good or outstanding painters. However, we were also shown a total lack of understanding of our viewers and their expectations concerning such undertakings, particularly when we take into consideration the fact that the current exhibition was already preceded by several outstanding shows of French art, all of which had greater artistic rank than the one in question. . . . And that is also why we all have such fond memories of the Contemporary Trends exhibition organised by the Dutch two years ago in the very same rooms of Zachęta. At least one third, if not half of the names were the same, but the dynamics of the two manifestations seems to be incomparable’.[2]

The exhibition was not prepared with the Polish audience in mind (like the Stedelijk Museum one), instead, it was thought up as a travelling show for the people’s democracy countries — Romania, Yugoslavia, Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Bulgaria. The documentation of the artists featured at the exhibition, deposited at the Bibliothèque Kandinsky in Paris, simply indicates Pays d’Est (Countries of the East) as the location of the exhibition. The presentation’s title mentioned in the documents is Montréal II.[3]

What does a Canadian city have to do with the European countries behind the Iron Curtain? The exhibition presented in Warsaw in 1968 was organised on the basis of a French art exhibition, prepared for the needs of the 1967 International and Universal Exposition in Montreal, an event organised to commemorate the Canadian Centennial. The French pavilion was built of concrete and steel, and the fact that it was surrounded by glass walls made it resemble a sculpture. It consisted of eight exhibition storeys with a total area of about 220,000 square metres. The main aim of the building was to reflect the ‘French genius, tradition and inventiveness.’ The lowest storey of the building encompassed a round swimming pool, a restaurant, a cinema, conference halls, as well as a transport and tourism exhibition. The ground storey held a honorary salon, a press room, an exhibition of outstanding French works around the world and the city of Paris. The 1st, 2nd and 3rd storeys were devoted to French science and technology, colour television, electronics, physics and astronomy.[4] The section devoted to art featured works ranging from the Roman era to the contemporary times, including a number of works loaned from the Louvre — Triple portrait of Cardinal de Richelieu by Phillippe de Champaigne, Magdalene with the Smoking Flame by Georges de la Tour, Bacchanal by Nicolas Poussin, works by Jacques-Louis David, and a painting by Fernand Léger.[5]

Słowo Powszechne mentioned the Canadian roots of the Warsaw exhibition: ‘At the end of the year, Warsaw was visited by an exhibition, which already had a history. Some of the exhibited works were previously shown at the 1967 World Expo in Montreal, where they served as the decoration of the French pavilion. In May of this year, the exhibition was shown in Bucharest, followed by a presentation in Yugoslavia. In October, it visited the National Museum in Kraków to finally arrive in the largest halls of Zachęta to stay there throughout November. The Central Bureau of Art Exhibitions also plans for the exhibition to be shown in other Polish cities, including Łódź, Rzeszów, Poznań and Wrocław. . . . 75 artists representing various trends and often opposite artistic directions were selected for the presentation — the works by many of them were shown in in 1966 during the Contemporary Trends exhibition at Zachęta’.[6]

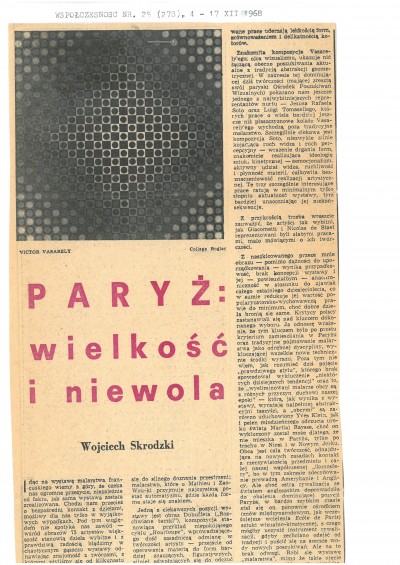

The exhibition prepared for people’s democracies consisted exclusively of contemporary paintings, namely 75 works by 75 artists of older and middle generation, including 36 of non-French origin. The majority of the works were created in 1965–1967. The most represented type of works were abstract paintings — lyrical and geometric abstraction, as well as surrealism, figurative paintings, expressionism and op art. Victor Vasarely’s work enjoyed the greatest interest of both the visitors and the press, which readily reproduced the painting. Express Wieczorny mentioned that: ‘It is impossible to start exploring the exhibition in any other way than by watching the enormous geometric painting presented in front of the entrance, which commands the visitors’ attention. Its creator, Vasarely, painter of Hungarian descent, together with the painter of Polish descent Henryk Berlewi competes for the title of originator of ‘op’ (optical) art. He divided the large canvas of the painting into 576 squares with circles inscribed in them’.[7]

The exhibition was unanimously criticised. Ewa Garztecka noticed its propaganda dimension, and her words gained a new meaning after the May events in France and the events of March in Poland. ‘All the sharp edges — everything that could shock or disturb — were omitted. Judging from the exhibition of contemporary French painting, the world these days is harmonious, lyrical, sometimes only shrouded with a mist of melancholy or wistful reverie.’[8] Maciej Gutowski, who had seen the exhibition in Kraków beforehand, shared her opinion: ‘it asks for decisions that are more brutal, less tasteful, but more intense — one could even say — less salon-like, sharper’.[9] According to his words, the exhibition presented the trends and tendencies of the 1950s, while the phenomena characteristic of the 1960s were overlooked.

Wojciech Skrodzki believed that the limiting of the scope of the exhibition solely to painting spoke to its anachronism. ‘Although the fierce competition with the Anglo-Saxon world led to the dethroning of Paris and stripping it of its dominant position, in a very short time, it once again became the international centre of visual and kinetic art like the earlier incarnations of École de Paris. It could become the city’s new weapon in the rivalry, if only there was a departure from tradition, if only they dared to go into the open waters of new explorations. However, they lack the courage to do so, which is why they present an exhibition of “painting”, despite the fact that such an approach excludes all the new spatial phenomena.’[10] Skrodzki also added that the works by Vasarely, Jésus Rafael Soto and Luis Tomasello ‘save the contemporariness of the exhibition only to a minimal extent, further highlighting its inconsistencies’. He also pointed out the works by Jean Dubuffet. ‘One of the most interesting works presented at the exhibition is Dubuffet’s painting (La brouette en surplomb — a composition, which serves as an example of work from the disturbing Hourloupe series, introducing quite a fundamental change in the artist’s work — a transition from the use of matter to more significant, figurative forms, referring to subconscious feelings, drawn sharply, obsessively imposing, with pungent colours of the contours.’ By featuring this work, the organisers made up for the shortcomings of the Contemporary Trends exhibition, since back then all the critics complained about the fact that not a single one of Dubuffet’s typical works was presented. In addition, one of the most voiced complaints was that that the exhibition was monotonous and boring.

It is worth noting the phenomena that were overlooked by artistic criticism. The exhibition featured a painting by Maryan, painted in 1960. The catalogue stated that the artist’s real name was Pinchas Burstein. He was born in 1927 in Nowy Sącz. This is how his work was described: ‘The anguish of wartime experiences has left an indelible mark on his work. He paints caricatured, yet tragic figures, sometimes enclosed in Kafkaesque spaces’.[11] The painting shows a figure with a long, grey beard, peeking into an empty room with walls covered with Stars of David. During the Second World War, Maryan was imprisoned in a concentration camp in Rzeszów, lived in Israel in 1947–1950, then moved to Paris, and later to New York (1962–1969). In the capital of France, he was close to the new figurative painting phenomenon, and in 1961, he took part in the exhibition of French graphic art in Poland.[12]

This piece, unnoticed by Polish critics, served as an excellent commentary on anti-Semitic actions in the country, stemming from the events of March of 1968. It seems that these events were alluded to in Tadeusz Chrzanowski’s text, who described the Kraków edition of the exhibition in Tygodnik Powszechny: ‘Nearly half of the artists featured in the exhibition were born outside France — in Ciudad Bolivar, Beijing and in Nowy Sącz. There is something really beautiful about this phenomenon — it is a great artistic democracy, which allows all races, colours and views to pool their efforts, which sums up the struggle undertaken not in the name of a single country or a people, but for all races and nations.’[13] Maryan was mentioned only in a single local paper — Nowiny Rzeszowskie: ‘The most interesting are the works by Pignon, Artais, Maryan and Jorn’.[14] In another issue of the newspaper, Jan Grygiel added: ‘The works representing the field of figurative painting are a definite minority, represented only by expressionists and surrealists, such as Pignon, Maryan, Arnas, Jorn, Dubuffet and Dado.’[15]

The exhibition was in line with the assumptions of the cultural policy of French Minister André Malraux and was organised by Création Artistique. On 8 February 1963, Malraux appointed a commission for the arts, which encompassed painters — André Beaudin and Jean Bazaine (whose works were shown at the exhibition in Warsaw), as well as André Chastel, Jean Lescure, François Mathey and Jean Paulhan. They were to comment on purchases and commissioning of artworks, tapestry designs and stained glass, furniture designs and public building decoration projects. In January 1966, Bernard Anthonioz — son of a sculptor, husband of Geneviève de Gaulle (Charles de Gaulle was her uncle), member of the cabinet of André Malraux from June 1958 on, and formerly associated with the Skira publishing house — became Inspector General of Création Artistique. Because of Anthonioz’s actions, the state Gobelins manufactures wove new tapestries based on the designs by Hans Hartung, Zao Wou-Ki and Mathieu (featured at the Warsaw exhibition). In 1967 he was appointed director of the National Centre for Modern Art, the aim of which was to develop the policy of openness towards contemporary art. It was Anthonioz who organised an exhibition of French painting presented in Warsaw in 1968. It is worth mentioning that during Malraux’s term, Odéon’s ceiling decoration was commissioned from André Masson, while Jean Bazaine was hired to create a large mosaic decorating the UNESCO building. Both artists took part in the Warsaw exhibition.[16]

Polish critics pointed out the elegance of French painting, as well as a lack of critical or disturbing accents. Meanwhile, the exhibition was organised a few months after the events of May 1968 in France, when students and workers took to the streets. André Malraux was one of the targets of the outcry and rebellion. He discredited himself with an unsuccessful attempt at ousting the founder of a Parisian film library associated with the ‘new wave’ in French cinema.[17] During the riots, he led a demonstration of government supporters.[18]

Let us close the history of the French exhibition in Warsaw by adding that in 1968, one of the guides presenting the works to the visitors was Anda Rottenberg, who later went on to become the director of Zachęta in 1993–2001, and who at that time won the Express Wieczorny award for best guide.[19]

The exhibition was also presented at the National Museum in Kraków (4–27 October 1968), the Museum of Art in Łódź (13 December–January 1969) and the Art House in Rzeszów (19 January–4 February 1969).

Karolina Zychowicz

Department of Documentation of Zachęta — National Gallery of Art

This text was prepared as part of the National Programme for the Development of Humanities of the Polish Minister of Science and Higher Education — research project The History of Exhibitions at Zachęta — Central Bureau of Art Exhibitions in 1949–1970 (no. 0086/NPRH3/H11/82/2016) conducted by the Institute of Art History of the University of Warsaw in collaboration with Zachęta — National Gallery of Art.

Bibliography

Source texts:

- Chrzanowski, Tadeusz. ‘Festiwal „École de Paris”’. Tygodnik Powszechny, no. 43, 1968

- ‘Dubuffet architektem’. Odgłosy, no. 5, 1969

- Garztecka, Ewa. ‘Nowoczesność już klasyczna. Wystawa współczesnego malarstwa francuskiego’. Trybuna Ludu, no. 328, 1968

- Grt. ‘Upominek dla najlepszej przewodniczki po „Zachęcie”’. Express Wieczorny, no. 294, 1968

- Grubert, Halina. ‘Malarstwo francuskie w „Zachęcie”’. Express Wieczorny, no. 279, 1968

- Grygiel, Jan. ‘Nowatorstwo i precyzja warsztatu. Współczesne malarstwo francuskie w Rzeszowie’. Nowiny Rzeszowskie, no. 21, 1969

- Gutowski, Maciej. ‘Współczesne malarstwo francuskie’. Dziennik Polski, no. 256, 1968

- KTT. ‘List z Warszawy’. Trybuna Robotnicza, no. 279, 1968

- Madeyski, Jerzy. ‘Wybór Francuzów’. Życie Literackie, no. 41, 1968

- ‘Malarstwo francuskie w „Zachęcie”’. Express Wieczorny, no. 279, 1968

- (Jel). ‘Wystawa współczesnego malarstwa francuskiego’. Nowiny Rzeszowskie, no. 17, 1969

- (k). ‘Wystawa malarstwa francuskiego’. Dziennik Polski, no. 236, 1968

- ‘Nowa ekspozycja Muzeum Narodowego’. Gazeta Krakowska, no. 237, 1968

- Rassalski, Stefan. ‘Francuzi w Warszawie’. Tygodnik Kulturalny, no. 49, 1968

- Romanowski, Ignacy Gustaw. ‘Malarstwo francuskie w Muzeum Sztuki’, Odgłosy, no. 3, 1969

- Rostworowski, Marek. ‘Druga Szkoła Paryska’. Kultura, no. 47, 1968

- Sempoliński, Jacek. ‘Wystawa malarstwa francuskiego’. Biuletyn Informacyjny ZPAP, no. 63–64, 1968

- Skrodzki, Wojciech. ‘Paryż: wielkość i niewola’. Współczesność, no. 25, 1968, s. 8

- W. K. ‘Panorama współczesnego malarstwa francuskiego’. Słowo Powszechne, no. 282, 1968

- Witz, Ignacy. ‘W „Zachęcie”’. Życie Warszawy, no. 284, 1968

- Współczesne malarstwo francuskie 1968, exh. cat. Warsaw: Centralne Biuro Wystaw Artystycznych, 1968

- ‘Współczesne malarstwo francuskie 1968’. Trybuna Ludu, no. 282, 1968

- ‘Wystawa współczesnego malarstwa . . .’. Głos Robotniczy, no. 297, 1968

- ‘Wystawa współczesnego malarstwa francuskiego’. Dziennik Łódzki, no. 297, 1968

Press mentions:

- Dziennik Polski, no. 225, 1968

- Dziennik Polski, no. 14, 1969

- Trybuna Ludu, no. 274, 1968

- Trybuna Ludu, no. 19, 1969

- Echo Krakowa, no. 239, 1968

- Echo Krakowa, no. 249, 1968

- Echo Krakowa, no. 250, 1968

- Gazeta Krakowska, no. 239, 1968

- Gazeta Krakowska, no. 254, 1968

- Tygodnik Kulturalny, no. 41, 1968

- Express Wieczorny, no. 269, 1968

- Express Wieczorny, no. 294, 1968

- Życie Warszawy, no. 273, 1968

- Życie Warszawy, no. 300, 1968

- Dziennik Ludowy, no. 270, 1968

- Trybuna Ludu, no. 313, 1968

- Kultura, no. 41, 1968

- Panorama Północy, no. 48, 1968

- Panorama Północy, no. 3, 1969

- Panorama Północy, no. 6, 1969

- Dziennik Łódzki, no. 297, 1968

- Dziennik Łódzki, no. 306, 1968

- Express Ilustrowany, no. 294

- 1968; Głos Robotniczy, no. 299, 1968

- Miesięcznik Literacki, no. 12, 1968

- Miesięcznik Literacki, no. 1, 1969

- Miesięcznik Literacki, no. 3, 1969

- Nowiny Rzeszowskie, no. 15, 1969

- Kamena, no. 4, 1969

- Kontynenty, no. 2, 1969

Artists:

Philippe Artias (1912–2002), Jean Bazaine [Jean-René Bazaine] (1904–2001), André Beaudin (1895–1979), Frédéric Benrath (1930–2007), Anna-Eva Bergman (1909–1987), Jean Bertholle (1909–1996), Huguette Bertrand (1925–2005), Pierre Bettencourt (1917–2006), Roger Bissière (1888–1964), Albert Bitran (1929), Victor Brauner (1903–1966), Camille Bryen (1907–1977), Aristide Caillaud (1902–1990), Pierre Charbonnier (1897–1978), Serge Charcoune (1888–1975), Roger Chastel (1897–1981), Dado [Miodrag Djurig] (1933–2010), Horia Damian (1922–2012), Olivier Debré (1920–1999), Jean Degottex (1918–1988), Jean Dewasne (1921–1999), Jean Dubuffet (1901–1985), Natalia Dumitresco (1915–1997), René Duvillier (1919–2002), Max Ernst (1891–1976), Maurice Estéve (1904–2001), Jean Fautrier (1898–1964), Claude Georges (1929–1988), Albertio Giacometti (1901–1966), Jean Gorin (1899–1981), James Guitet (1925–2010), Simon Hantai (1922–2008), Hans Hartung (1904–1989), Jean Helion (1904–1987), Auguste Herbin (1882–1960), André Heurtaux (1898–1983), Alexandre Israti (1915–1991), Asger Jorn (1914–1973), Wilfredo Lam (1902–1982), André Lanskoy (1902–1976), Charles Lapicque (1898–1988), Jean Le Moal (1909–2007), Albert Le Normand (1915–2013), Marcel Lubtchansky [Loubchansky] (1917–1988), Alberto Magnelli (1888–1971), Alfred Manessier (1911–1993), Maryan [Pinchas Burstein] (1927–1977), André Masson (1896–1987), Georges Mathieu (1921–2012), Roberto Matta [Roberto Antonio Sebastian Matta Echaurren, (1912–2002), Jean Messagier (1920–1999), Richard Mortensen (1910–1993), Georges Noël [Bédard George] (1924–2010), Luc Peire (1916–1994), Edouard Pignon (1905–1993), Serge Poliakoff (1906–1969), Louis Pons (1927–1985), Mario Prassinos (1916–1985), Jean-Paul Riopelle (1923–2002), Suzanne Roger (1898–1986), Michel Seuphor (1901–1999), Joseph Ŝíma (1891–1971), Gustave Singier (1909–1984), Jésus Rafael Soto (1923–2005), Pierre Soulages (1919), Nicolas de Staël (1914–1955), Árpád Szenes (1897–1985), Pierre Tal-Coat (1905–1985), Luis Tomasello (1915–2014), Raoul Ubac (1910–1985), Bram van Velde (1895–1981), Victor Vasarely (1906–1997), Maria Helena Vieira da Silva (1908–1992), Wols (Otto Alfred Schultze Batman, 1912–1951), Zao Wou Ki (1921–2013)

[1] Maurice Allemand, [untitled], in Współczesne malarstwo francuskie 1968, exh. cat., Warsaw: Centralne Biuro Wystaw Artystycznych, 1968, n.pag. [p. 12].

[2] Ignacy Witz, ‘W „Zachęcie”’, Życie Warszawy, no. 284, 1968.

[3] Cf. documentation: ANNA EVA BERGMAN, PIERRE CHARBONNIER, BÉDARD GEORGE dit GEORGES NOËL, ARTIAS PHILIPPE. Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Paris.

[4] http://expo67.ncf.ca/expo_france_p1.html (accessed: 13 October 2017).

[5] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kHHf64rbXkQ (accessed 13 October 2017).

[6] W. K., ‘Panorama współczesnego malarstwa francuskiego’, Słowo Powszechne, no. 282, 1968.

[7] ‘Malarstwo francuskie w „Zachęcie”’, Express Wieczorny, no. 279, 1968.

[8] Ewa Garztecka, ‘Nowoczesność już klasyczna. Wystawa współczesnego malarstwa francuskiego’, Trybuna Ludu, no. 328, 1968.

[9] Maciej Gutowski, ‘Współczesne malarstwo francuskie’, Dziennik Polski, no. 256, 1968.

[10] Wojciech Skrodzki, ‘Paryż: wielkość i niewola’, Współczesność, no. 25, 1968, p. 8.

[11] Współczesne malarstwo francuskie 1968, exh. cat., Warsaw: Centralne Biuro Wystaw Artystycznych, 1968, n.pag. [p. 22].

[12] Cf. documentation MARYAN [Burstein, Maryan Pinchas, dit Maryan], Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Paris.

[13] Tadeusz Chrzanowski, ‘Festiwal „École de Paris”’, Tygodnik Powszechny, no. 43, 1968.

[14] (Jel), ‘Wystawa współczesnego malarstwa francuskiego’, Nowiny Rzeszowskie, no. 17, 1969.

[15] Jan Grygiel, ‘Nowatorstwo i precyzja warsztatu. Współczesne malarstwo francuskie w Rzeszowie’, Nowiny Rzeszowskie, no. 21, 1969.

[16] Charles-Louis Foulon, Marie-Claude Morette-Maillant, ‘Création artistique et commandes publiques’, in Charles-Louis Foulon, Janine Mosuz-Lavau, Michaël de Saint-Cheron, Dictionnaire Malraux, Paris, 2011, pp. 201–203.

[17] Jean-Yves Potel, ‘Ten śliczny miesiąc maj’, trans. Maria Braunstein, in Rewolucje 1968, ed. Hanna Wróblewska, Maria Brewińska, Zofia Machnicka, Joanna Sokołowska, Warsaw: Zachęta Narodowa Galeria Sztuki, 2008, p. 192.

[18] Ibid., p. 197.

[19] Grt, ‘Upominek dla najlepszej przewodniczki po „Zachęcie”’, Express Wieczorny, no. 294, 1968.

1968 Exhibition of Contemporary French Painting

12.11 – 03.12.1968

Zachęta Central Bureau of Art Exhibitions (CBWA)

pl. Małachowskiego 3, 00-916 Warsaw

See on the map