In 1845, Henry David Thoreau, the 19th-century thinker, ascetic, moralist, rebel and mystic, a symbol of American individualism, who postulated starting the world anew and changing humanity — among others through getting closer to nature and returning to the primitive forms of life — decided to indeed return to the simple life in nature1. For two years, two months and two days, he lived in the forest on the shore of Walden Pond, near his hometown of Concord. He wrote: ‘I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.’2 Thoreau led a simple existence, fulfilling his basic needs through the work of his hands, which did not require a lot of effort. He observed nature, read, reflected. During this time, he also began to write his most famous work, Walden, or Life in the Woods. Thoreau gave his book a well thought-out structure. He described the experiences of two years of a solitary life in the chapters that describe specific actions and the seasons. Critics of the book emphasise that the author did not want to change the world for the better, nor did he postulate that everyone should become a hermit. He simply suggested a simple life in the world as it is. Today, we would say that he revealed to his readers alternate paths of existence (personal development). ‘I never in all my walks came across a man engaged in so simple and natural an occupation as building his house. . . .The most interesting dwellings in this country, as the painter knows, are the most unpretending, humble log huts and cottages of the poor commonly; it is the life of the inhabitants whose shells they are, and not any peculiarity in their surfaces merely, which makes them picturesque.’3 Thoreau built his hut in the woods using lumber from local trees, as well as elements recovered from an abandoned house nearby.

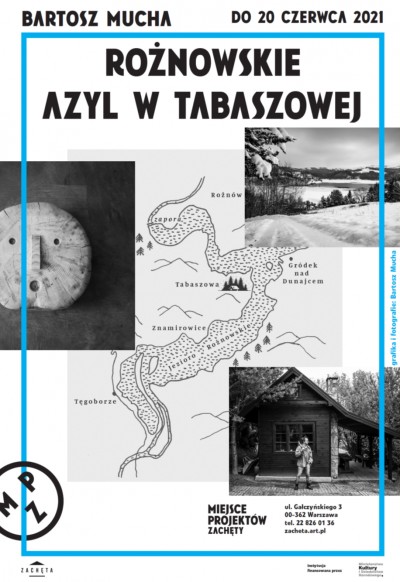

In the title of his exhibition at the Zachęta Project Room, Bartosz Mucha consciously references Thoreau, his experiment and book. Mucha’s house in the lap of nature also used local lumber, and its origins were fragments of a gazebo left by the previous owners. (The architectural model of the house is the central element of the exhibition.) The ecological approach can be seen in the entire project: the artist used second-hand windows and recycled the waste lumber left over from construction. He used it to create sculptures with a raw character, resembling ritual masks, totems, or simplified representations of heads. He set them up in the space of the gallery on classic museum pedestals or hung them on the walls. The elements they were carved or assembled from have been stained with shades of brown, soot and grey, or they retain the natural wood colour. The artist traces the genesis of these objects to the obsessive drawings of faces with which he has unknowingly filled sheets of paper (conference drawings) for years. In the exhibition, they become three-dimensional. These are Bartosz Mucha’s first experiments with wood sculpture. The objects displayed in the gallery space somewhat resemble an exhibition of tribal art or a show of sculptures inspired by them created by modern artists, such as Pablo Picasso, and cartoon characters. The joy of experimentation that accompanied the artist is written into them. Masks are sometimes called visual vehicles of transformation. In the case of Bartosz Mucha, transformation may refer to the change in direction of his creative interests, which the exhibition at the Zachęta Project Room shows. The massive stools created as part of the same project are carved from wooden stumps and resemble folk craft products. The exhibition features two such seats with deliberately primitive forms.

Mucha writes: ‘The house was created spontaneously, based on sketches and rough measurements’. During the construction, the artist modified some elements, adapting them to the specific conditions of the plot or practical difficulties he encountered. The building fit naturally into the existing terrain and nature. The house has electricity, basic furniture and equipment. The view of the forest, the distant Tatra Mountains and Lake Rożnowskie is breathtaking, prompting reflections on the power of nature. A bonfire can be lit in front of the house, allowing for an atavistic contemplation of this element. Bartosz Mucha gives viewers the opportunity to warm themselves by a virtual fire in the underground section of the gallery.

When creating his projects, Bartosz Mucha is accompanied by a desire to improve the quality of human life; his motivation is often the search for safe places, the creation of refuges. In the case of his latest works, the author seems to be saying that a refuge may be not only real architecture — a house — but also nature, in which the troubled soul of contemporary humans can find comfort and escape — including from pandemic fears).

Magda Kardasz

1 On the basis of Halina Ciepielińska’s introduction to her translation of the book: Henry David Thoreau, Walden, czyli życie w lesie, trans. Halina Ciepielińska, Poznań: Rebis, 2019.

2 Henry David Thoreau, Walden, or Life in the Woods, New York: Cosimo, 2009, p. 59.

3 Ibid., p. 29, 30.

The artist infront of the completed house, photo: Bartosz Mucha