Witkacy’s company also served to make money. He created a set of rules defining the types and prices of portraits offered, which also regulated the complicated painter–client relationship. One of the funniest rules stated, ‘The client must be satisfied. Misunderstandings are not permitted. . . . If the company allowed itself the luxury of listening to clients’ opinions, it would have gone mad a long time ago’. A dissatisfied client could return the painting to the author, but forfeited the down payment. Salamon’s company tries to satisfy the client, but not at any price. The author sometimes corrects a painting to improve the mood of a good friend, and in cases of extreme dissatisfaction with a portrait, cover it up with paint. He claims that the best portraits are those of people he knows. Witkacy, in turn, reserved for his friends the metaphysical category C — portraits painted under the influence of consciousness-expanding substances, going beyond the categories of conventional representation or idealisation of image.

Witkiewicz was particularly fond of painting women, especially those he adored. Salamon admits that it is easier for him to paint men with characteristic features, sharing the opinion of Edward Dwurnik, who said that the most difficult portrait to paint is that of a beautiful woman. Ania, the artist’s girlfriend, whom he has been drawing for years, is the exception to this rule.

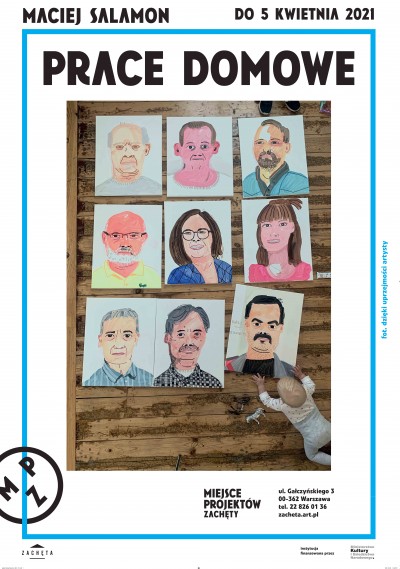

In the initial stage of the pandemic, information about the services provided by Salamon’s portrait company spread by gossip and through Facebook among acquaintances — mainly in the closest, artistic circles. We can risk a statement that over these past few months, the artist managed to paint a collective portrait (over 100 paintings) of the creative people from the 30+ generation living in the Tri-City. The company advertises online, so there are also clients from outside these circles. The prices of the paintings are not high. The artist paints small-format portraits in the form of busts. Some clients commission images of their idols — such as Kanye West or Jack White.

It is clear that drawing is Salamon’s element. The portraits are quick sketches, built with decisive lines. They are full of impastos of colours, creating harmonious combinations. A painting is usually created during one session, although some require several. (According to Witkacy’s formal categorisation, Salamon’s portraits could be assigned to type B plus: ‘characteristic portraits, but without a shade of caricature, made with more freedom. The work is more sketch-like than type A, with a certain shade of characteristic features, which does not rule out “prettiness” in women’s portraits’. The attitude towards the model is objective’. The author himself says, ‘My portraits should be treated as interpretations of the subjects according to Salamon’.

The pandemic reality has limited direct human contact — including that of the painter and the model, hence the need to paint from photographs, greater use of social media for advertising, sending completely paintings via courier. Salamon’s portrait company operates in his home — the artist, like most parents working remotely today, divides his time between painting and trivial housework, broadening the definition of the term. However, unlike most of the people working from home described above, the artist appreciates this way of creation.

As the pandemic months passed, the popularity of M. Salamon’s portrait company began to drop, as did the public’s interest in virtual exhibitions, concerts or online performances. We have been talking to Maciek Salamon about an exhibition in the Zachęta Project Room for several years. After ‘the artist regained faith in painting’, the idea to show the portrait project, as well as other recent paintings, in our gallery was born. The exhibition is titled Housework. The artist suggested playing with the ‘site specific’ idea: painting portraits of all the people who make it possible for viewers to see exhibitions in the gallery — those on the front line, like the curator and the assistant, but also those usually absent from the opening, such as exhibition production department staff, installers, carpenters and electricians. He also captured the people who serve the daily operations of the gallery, such as the guard and the janitor. And so a democratic gallery of portraits of ‘all the people of the Zachęta Project Room’ was hung on the walls. Engraved plaques reveal their names.

Among Salamon’s other new paintings shown at the exhibition, those from the Cheap Clothes series stand out, depicting vintage jumpers with eccentric patterns, so valued by the city’s fashionistas or denim jackets with heavy metal band logos (original self-made versions and their imitations from chain stores). Among them we find a jacket with the names of the bands in which the author of the exhibition has performed. There are also paintings and a film inspired by the art of tattooing, which fascinates Salamon and which he practices. Other recently created canvases subjectively copy classic works from the history of art. They can be read as another voice in the discussion about the meaning of painting today.

In the lower rooms of the exhibition, the artist shows videos that can help viewers learn to draw. He uses representations of pregnant woman and woman holding a child as his subjects (using ‘home’ models). The patient teacher guides the student, step by step, revealing the difficulties, secrets and drawing tricks, while also referencing classic painting representations. The project jokingly comments on the world of YouTube tutorials, thanks to which you can learn how to do practically anything. They are especially useful in times of pandemic boredom caused by spending more time at home than usual. The tour of the exhibition ends in an interactive space where the viewer, following the instructions from the film (or not) can draw their own composition. Hanging it on a specially allocated wall, they in a way become a co-author of the exhibition. Maciej Salamon is a tireless promoter of the noble art of drawing.

Magda Kardasz

1 ‘“Poczucie misji spada proporcjonalnie do liczby osób w rodzinie”. Rozmowa Macieja Salamona z Emilią Orzechowską’, NN6T, 12 August 2020.